Blue Begonias: More Than Meets the Eye

Begonia burkillii dark form

Evolutionary Function, Species Distribution, and Cultivation for Enhanced Iridescence

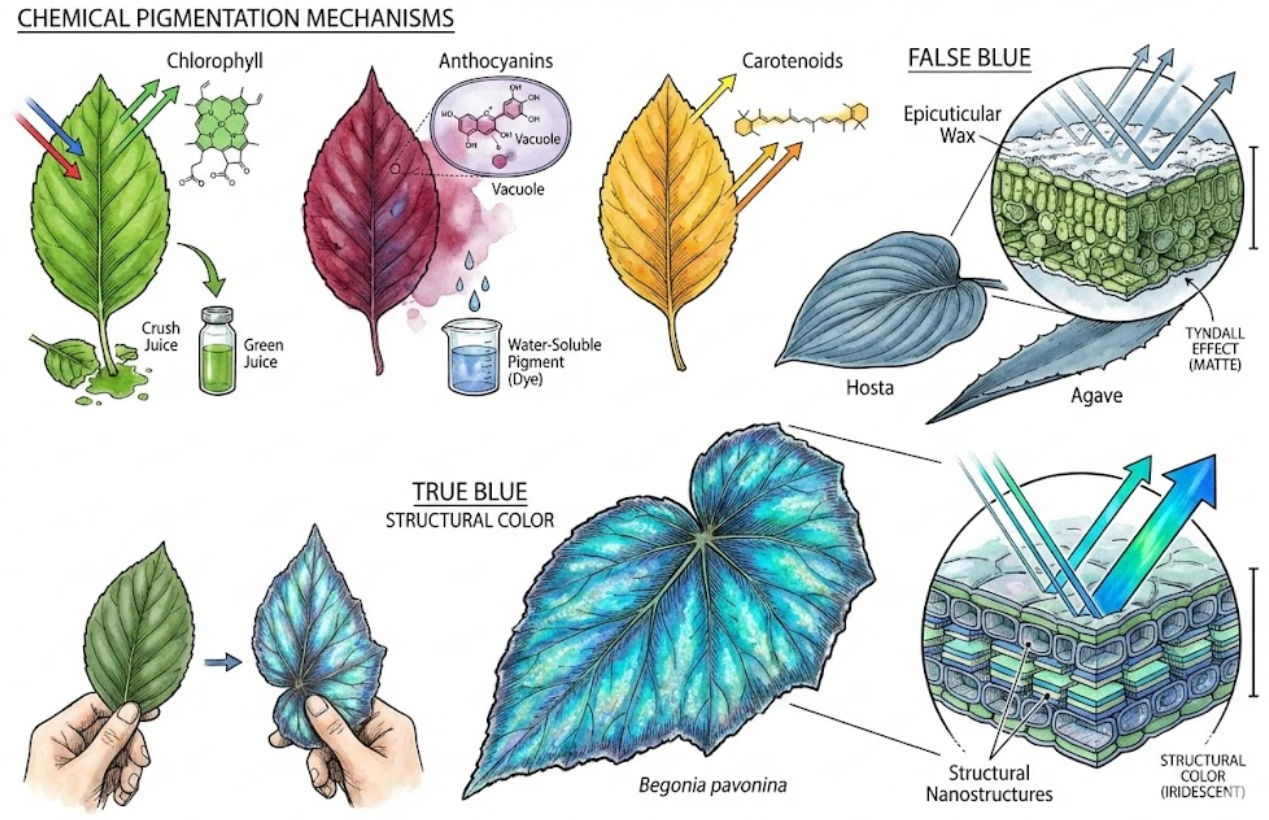

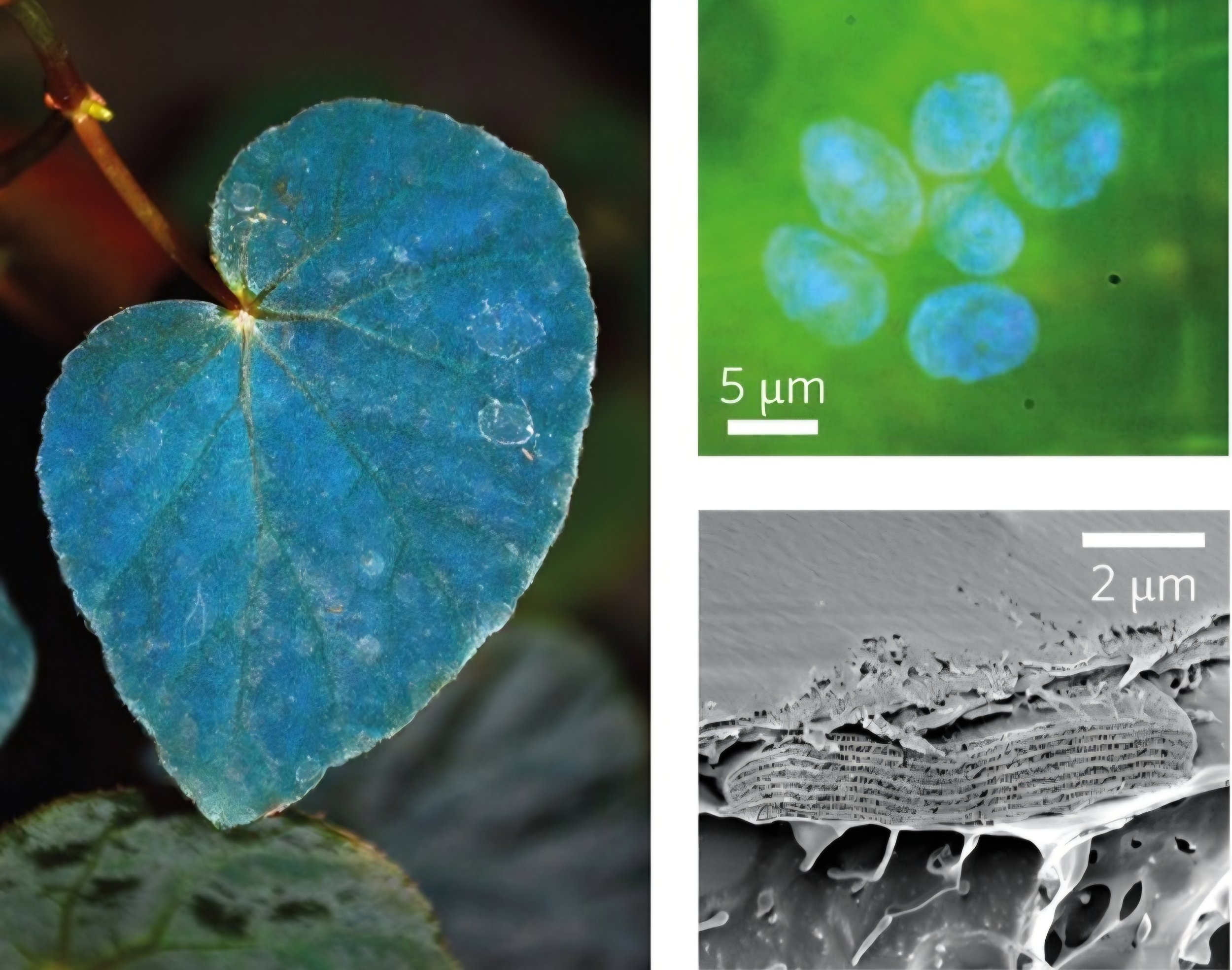

Unusual blue or blue-green iridescence in the leaves of some understory plants has fascinated botanists since early observations in the late twentieth century. Within the diverse genus Begonia (Begoniaceae), this shimmer is now understood not as a pigment-based colour but as structural colour arising from specialised organelles called iridoplasts - modified chloroplasts with photonic properties that interact with light in ways ordinary chloroplasts do not [3,5].

We want to help you increase your scientific knowledge about these organelles: the evolutionary pressures shaping them, which Begonia species possess them, and how to cultivate begonias in ways that promote their development and visibility.

What Are Iridoplasts?

Cellular and Structural Basis

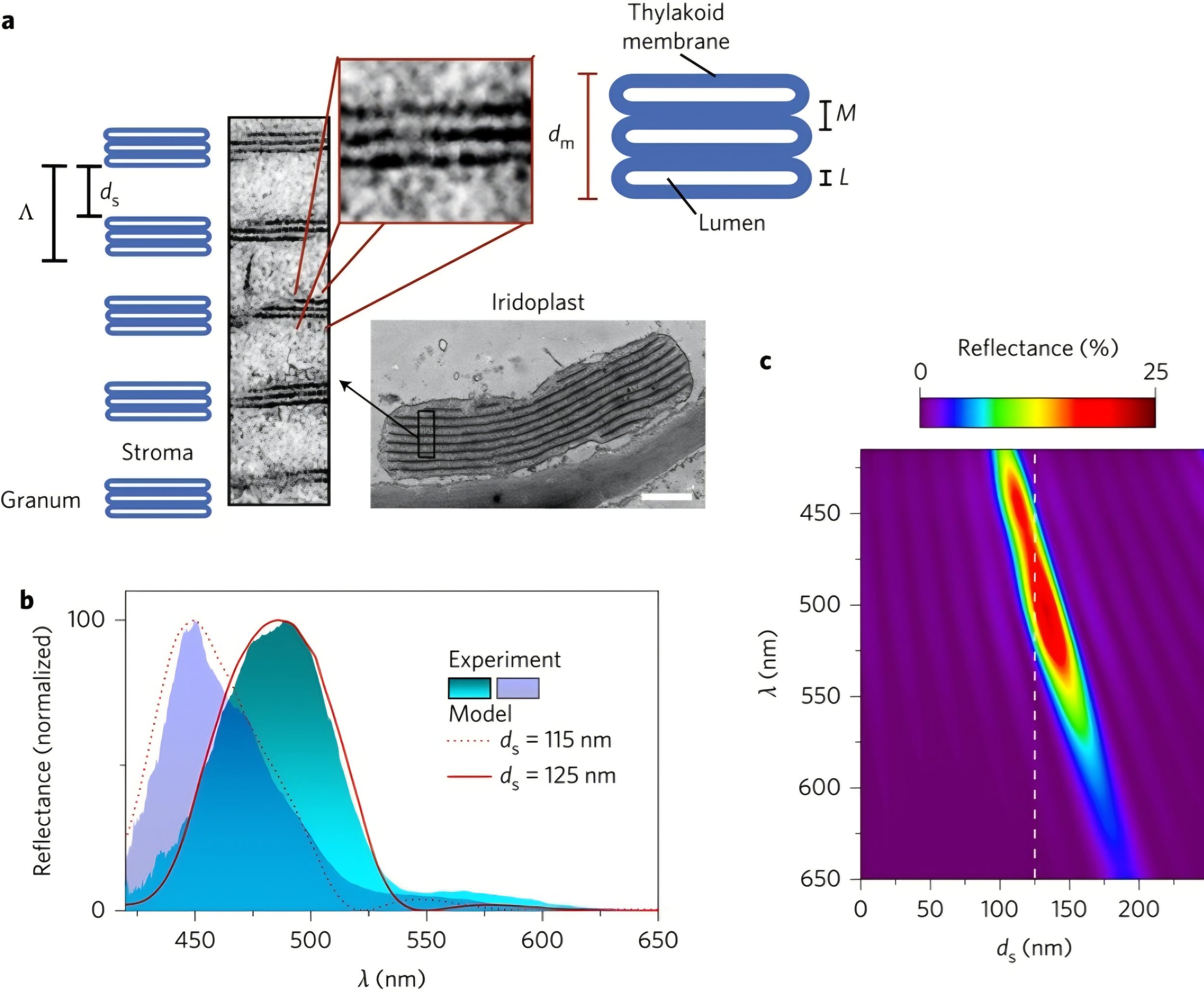

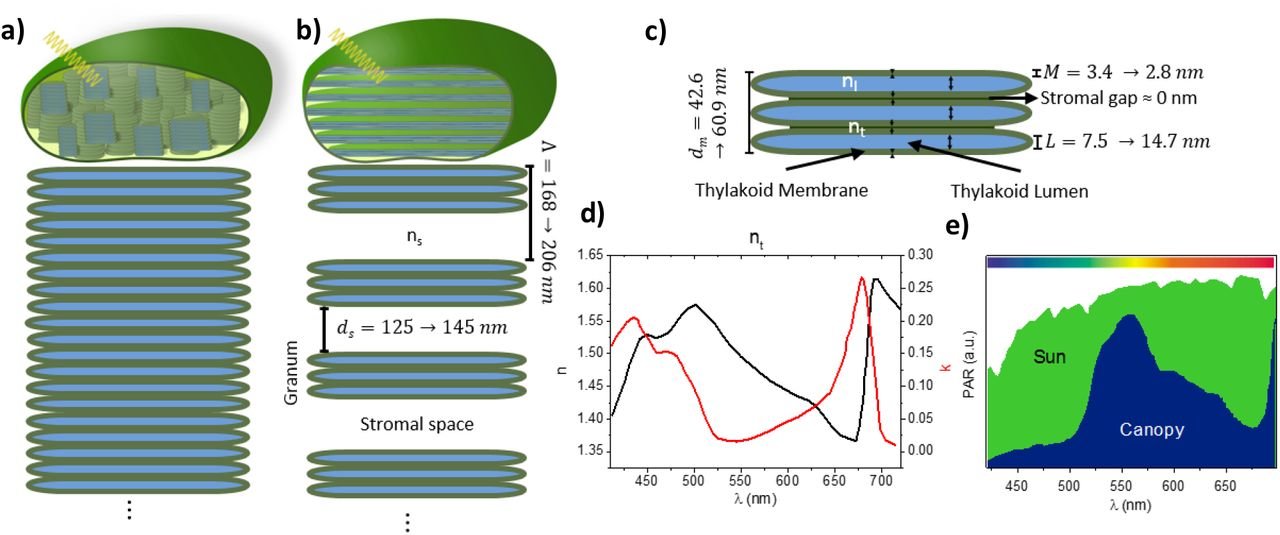

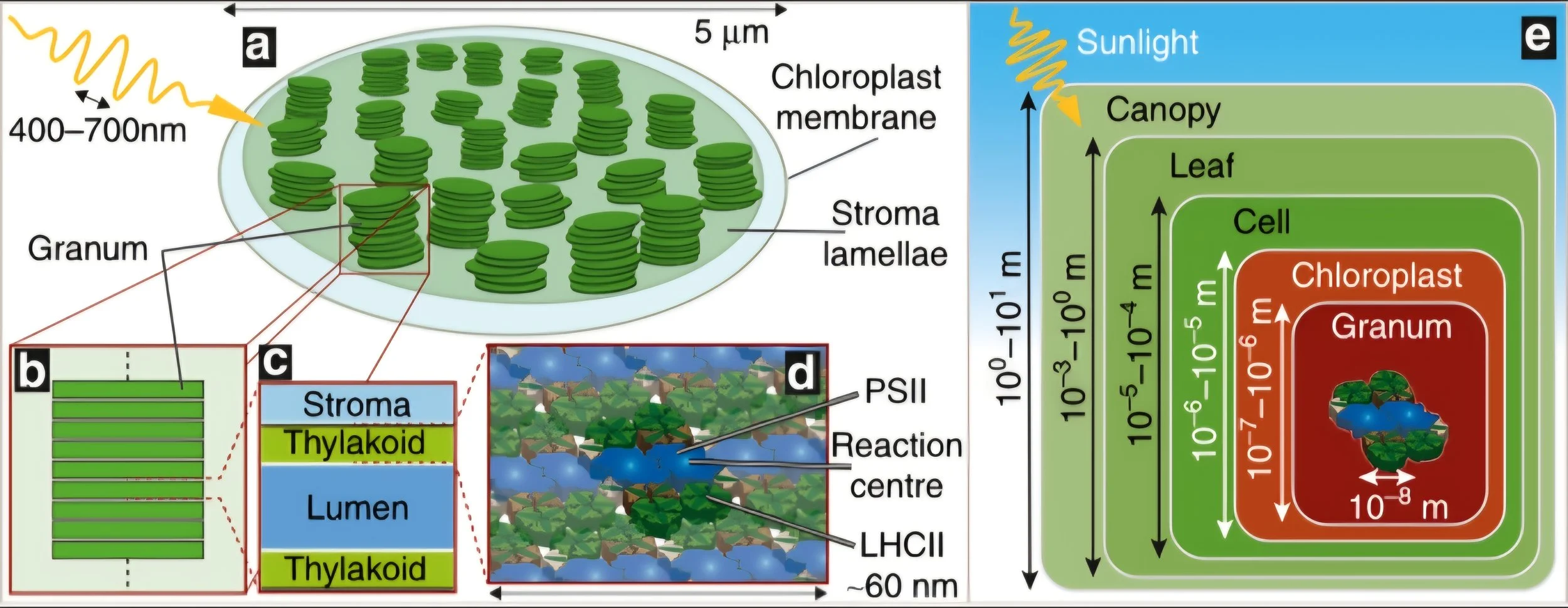

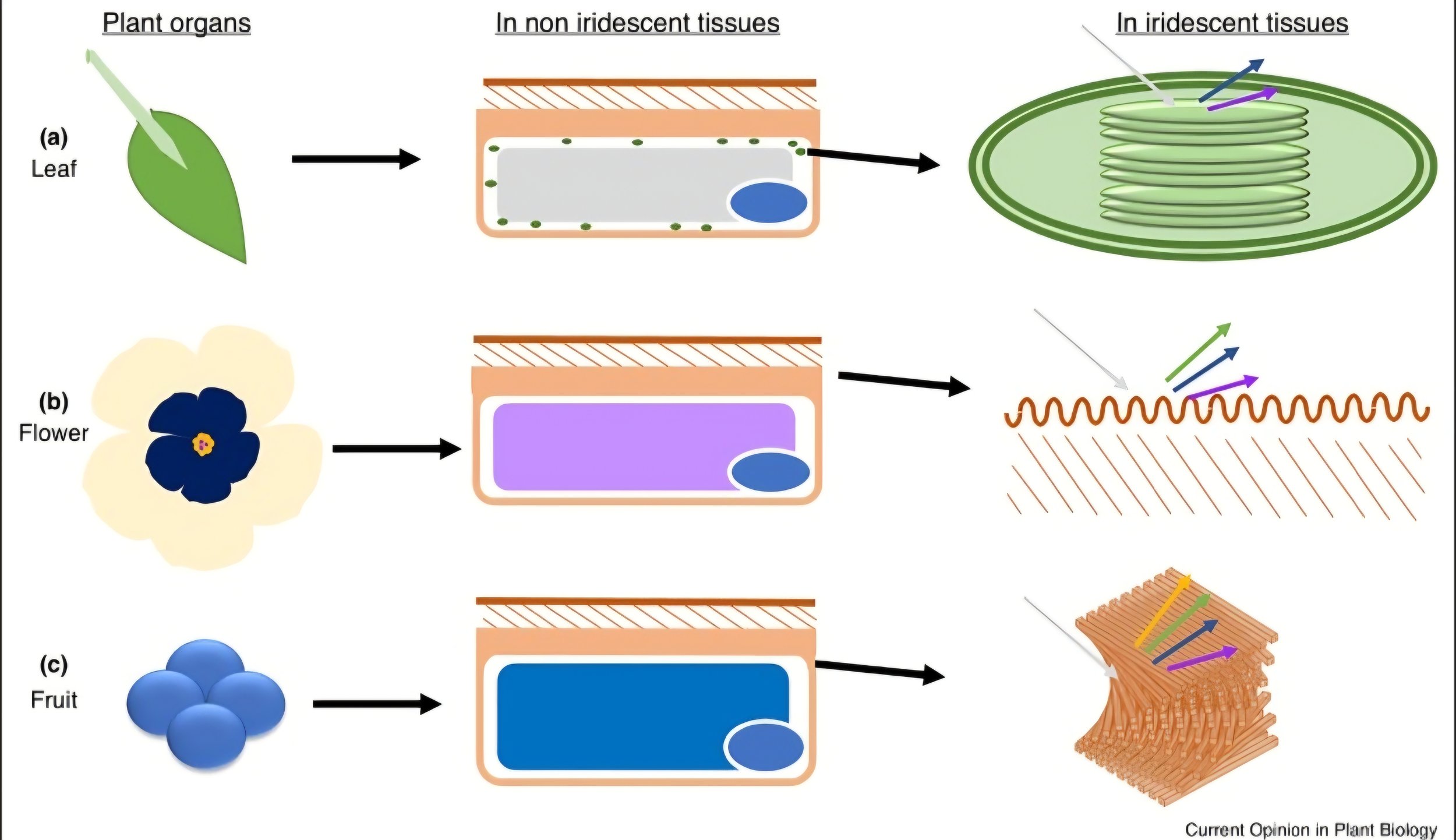

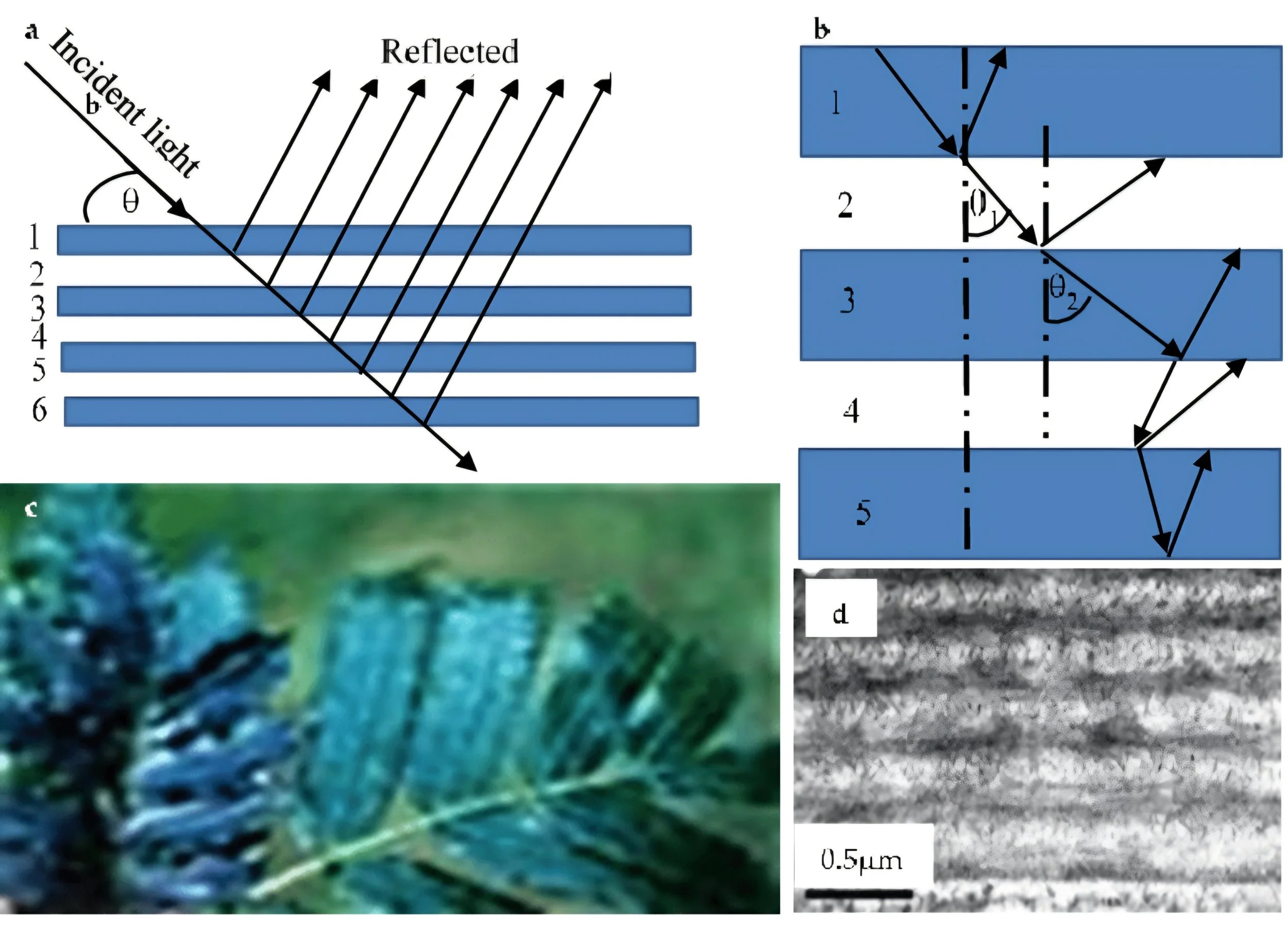

Iridoplasts are modified plastids - specialised forms of chloroplasts - found primarily in the adaxial (upper) epidermal cells of leaves in certain shade-dwelling Begonia species. Unlike canonical mesophyll chloroplasts, which have loosely arranged thylakoid membranes, iridoplasts contain highly regular, stacked layers of thylakoid membranes separated by uniform stromal gaps. This regular spacing creates a one-dimensional photonic crystal - a biological structure that interacts with light wavelengths through constructive and destructive interference [3].

The name “iridoplast” arises from the organelle’s iridescent appearance under microscopy - the ordered stacks reflect specific wavelengths of light in a way similar to thin films or photonic crystals engineered in physics and photonics [3,6].

Mechanism of Structural Colour

The multilayered thylakoid architecture acts as a photonic structure: wavelengths corresponding to the periodicity of the layers are reflected, while others are preferentially transmitted for photosynthesis. In classic blue iridescent Begonia, this results in light predominantly in the blue-to-blue-green spectrum being reflected, producing the visible iridescence [3].

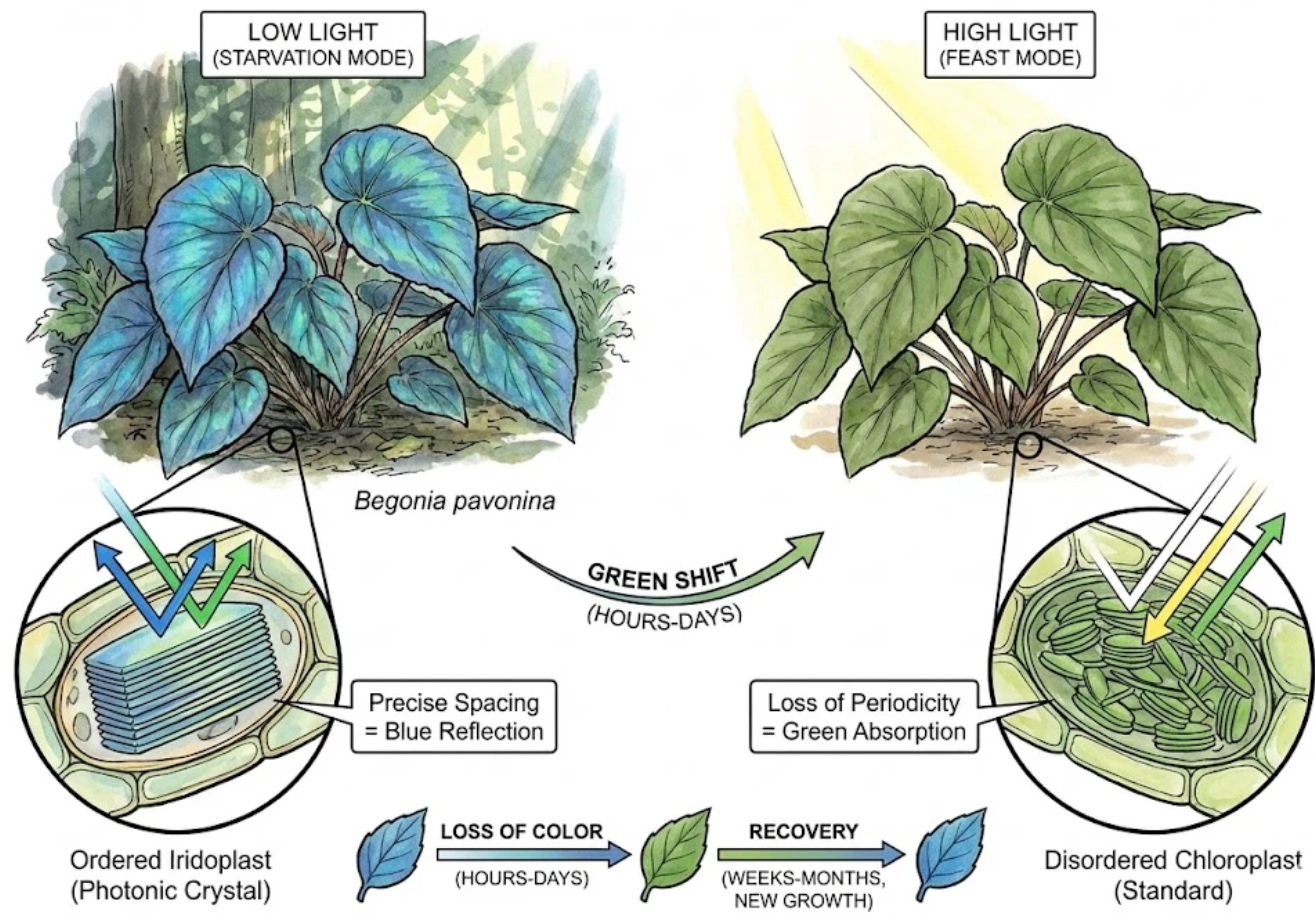

Iridoplast Structure (Microscopic Diagram)

What you’re seeing:

Stacked thylakoid membranes arranged in evenly spaced layers.

These layers act as a photonic crystal, reflecting specific wavelengths of light (often blue/blue-green) - the basis of iridescence.

A comparison with normal chloroplasts shows the difference: iridoplasts have highly ordered lamellae vs typical randomly arranged thylakoids.

Evolutionary Purpose of Iridoplasts

Adaptation to Shade

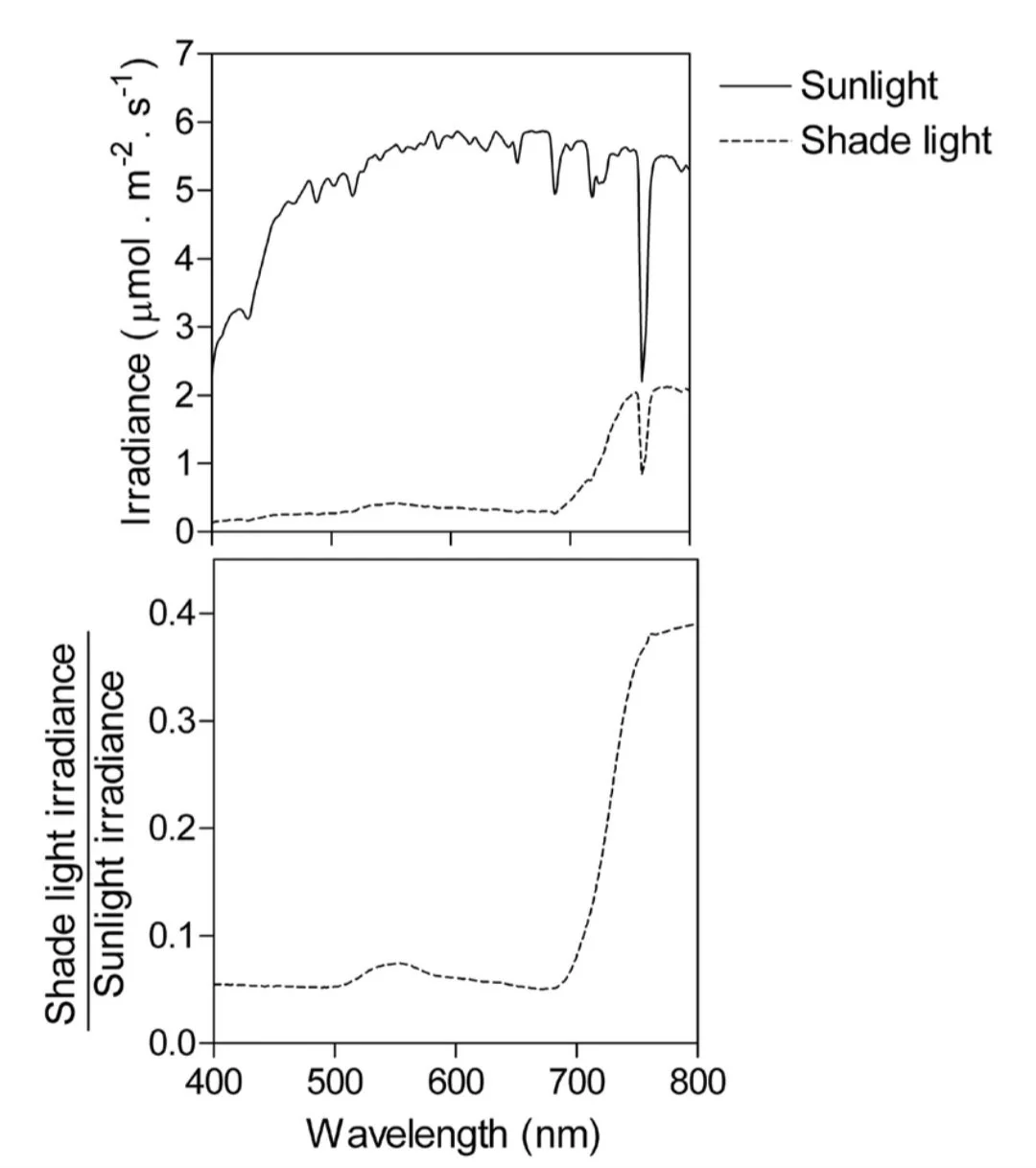

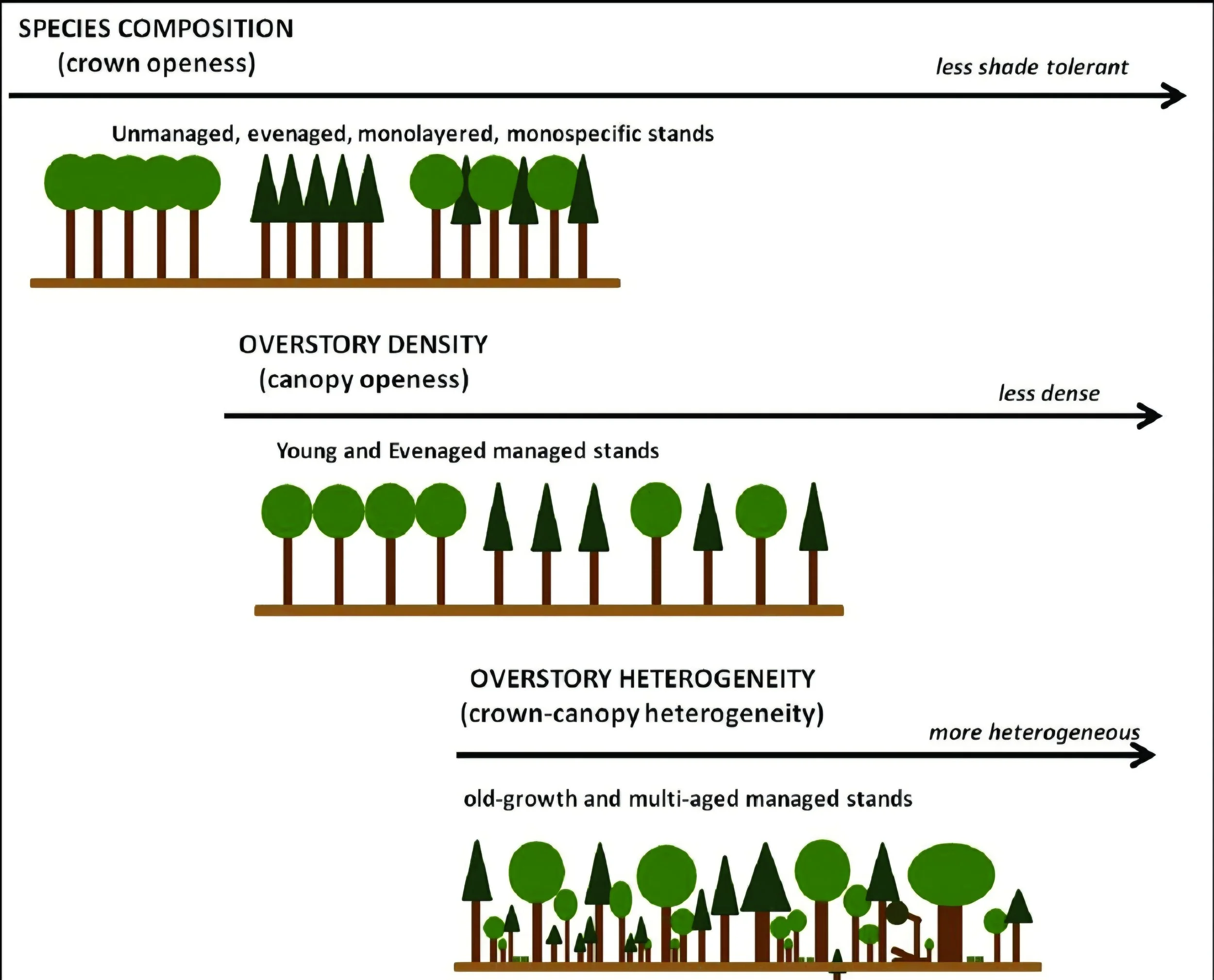

The prevailing and best-supported functional hypothesis - backed by detailed experimental evidence - is that iridoplasts are an adaptation to low-light environments, such as the forest understorey where many iridescent Begonia species grow. In these habitats, the canopy above filters much of the direct sunlight, leaving a light spectrum poor in blue wavelengths and rich in green [3,2].

The photonic crystal structure of iridoplasts has two principal benefits under these conditions:

Enhanced Light Capture at Green Wavelengths:

The layered thylakoid structure can effectively slow down and scatter the predominantly green photons that penetrate to the understorey, increasing their interaction time with photosynthetic pigments. This improves capture of wavelengths that ordinary chloroplasts inefficiently absorb [3].

Increased Quantum Yield in Low Light:

Studies have shown that the presence of iridoplasts can enhance the quantum yield of photosynthesis (the efficiency with which absorbed photons drive the photosynthetic reaction) by 5-10% under low light relative to species without such structures [3].

Together, these effects support a selective advantage in shaded environments - plants with iridoplasts can fix carbon and grow where ordinary chloroplast-bearing plants would be light-limited [3].

How Iridoplasts Work (Light Interaction Diagram)

Key concepts illustrated:

Incident light passes into leaf tissues.

Photonic layers in the iridoplast reflect specific wavelengths via constructive interference.

Other wavelengths are transmitted deeper where they are used for photosynthesis.

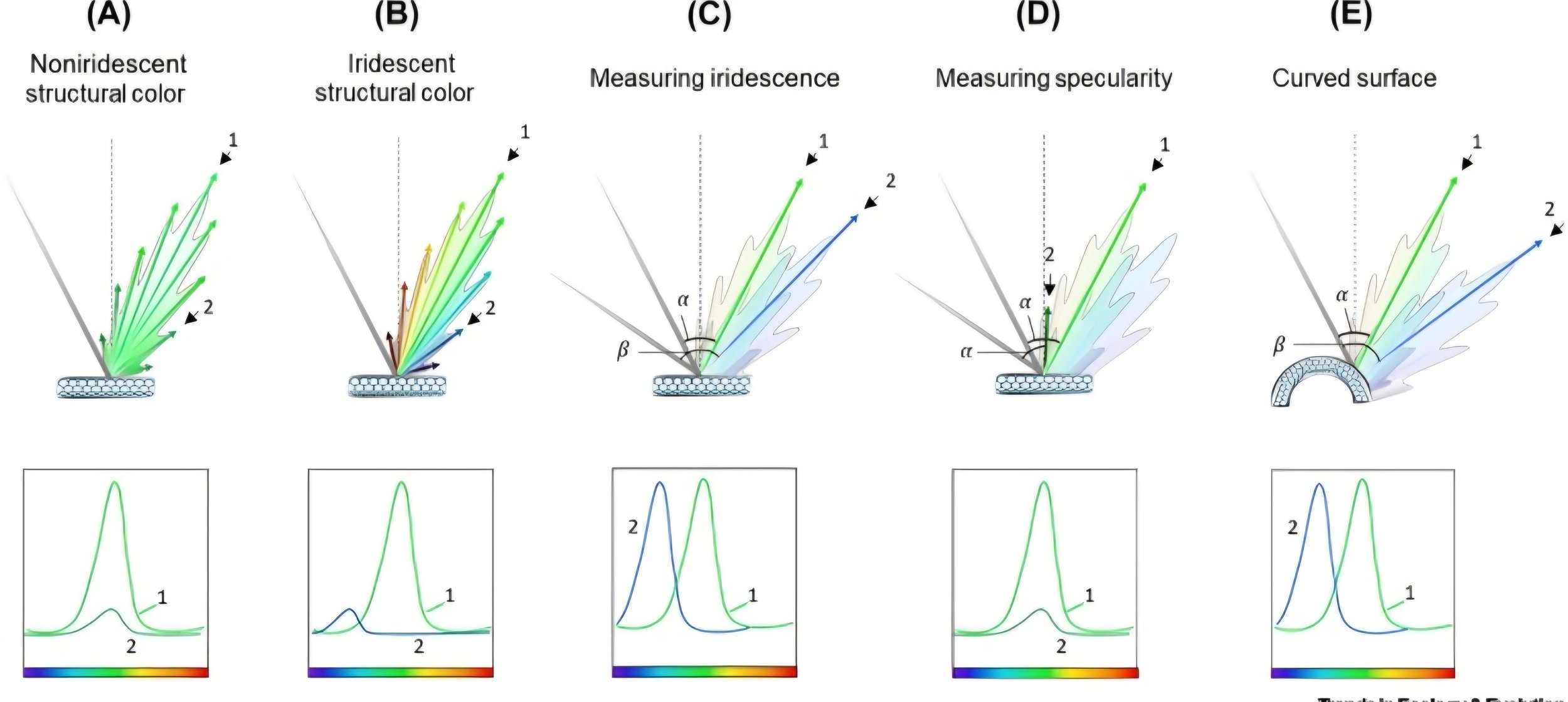

Structural Colour as Secondary/Incidental Trait

Importantly, the iridescence visible to human observers is not thought to be the primary evolutionary driver; rather, it is a by-product of these photonic structures. The blue or green iridescence is an optical consequence of the thylakoid spacing rather than a signal for pollinators or herbivores, though the latter hypotheses have occasionally been proposed in broader literature on structural colour in plants [6].

Species That Contain Iridoplasts

Begoniaceae Family Distribution

Iridoplasts (also referred to as “lamelloplasts” in some literature when emphasising the stacked lamellar structure) have been documented within Begonia and its sister genus Hillebrandia. The family Begoniaceae therefore includes taxa with these specialised plastids [5].

Species with Confirmed Iridoplasts

Detailed ultrastructural surveys reveal the following patterns from major peer-reviewed studies:

22 taxa of Begonia and the monotypic Hillebrandia sandwicensis were identified as containing iridoplasts in epidermal cells, even if not all produced visible iridescence [5].

Of these 22, nine Begonia taxa displayed conspicuous blue to blue-green iridescent leaves when viewed macroscopically, including B. melanobullata, B. nepalensis, B. austrotaiwanensis, B. edulis, B. pavonina, and B.rockii [5].

Begonia pavonina - the classic “peacock begonia” has been a focal model for iridoplast research due to its striking blue iridescent leaves and clear adaptive responses to low light.

Begonia grandis × B. pavonina hybrid - used experimentally in multiple investigations due to robustness and stable expression of iridoplasts [3].

Other species analysed for iridoplast content include taxa with both visible and cryptic structural colour. Through transmission electron microscopy, structures consistent with iridoplasts have been observed even when the leaves appear green to the naked eye [6].

Beyond Begonia

Iridoplast-like structures are not unique to Begoniaceae. Few other lineages, such as Phyllagathis rotundifolia (Melastomataceae) and some lycophytes and ferns, also exhibit structurally coloured plastids, though the ecological contexts may differ [1,4].

Physiology, Plasticity, and Functional Nuances

Functional Performance Relative to Mesophyll Chloroplasts

Iridoplasts are found in the epidermal leaf layers, which generally have lower photosynthetic capacity than mesophyll tissues. Studies indicate that although individual iridoplasts may be less efficient at photosynthesis than mesophyll chloroplasts in relative terms, their enhanced ability under low light increases the overall carbon acquisition of shade-adapted taxa [5].

Plasticity and Environmental Response

Research suggests that the development and ultrastructural integrity of iridoplasts can be plastic in response to light conditions:

Under very low light, iridoplast layers remain highly regular, enhancing interference effects.

Under higher light conditions, the ordered arrangement can become disordered, reducing visible iridescence and functional benefits, indicating an adaptive trade-off [6].

This plasticity has implications for both ecology and cultivation - iridoplast expression is environmentally regulated rather than strictly genetically fixed.

Cultivation: Enhancing Iridoplast Development in Home Growing

For horticultural enthusiasts wishing to cultivate begonias with strong iridescent character, environmental conditions play a crucial role. Unlike pigment traits genetically determined and stable, the iridoplast architecture depends on light environment cues.

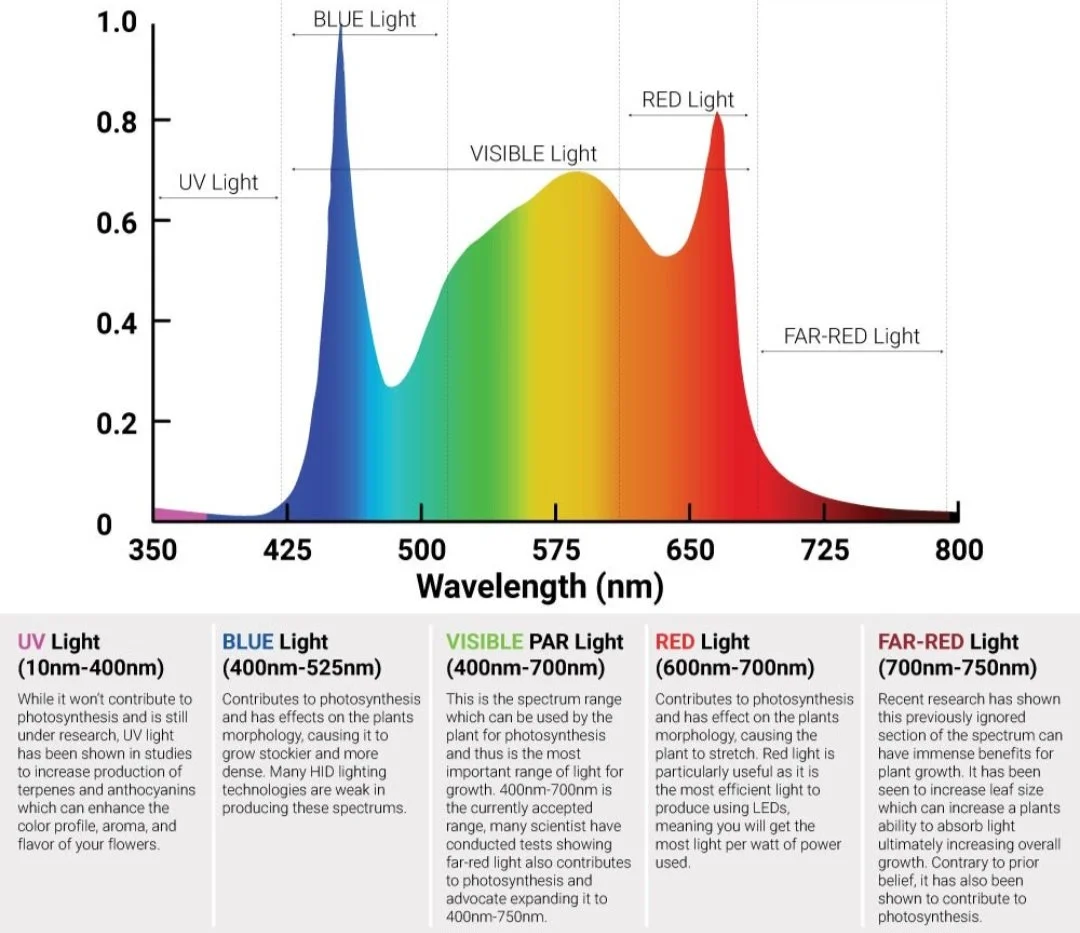

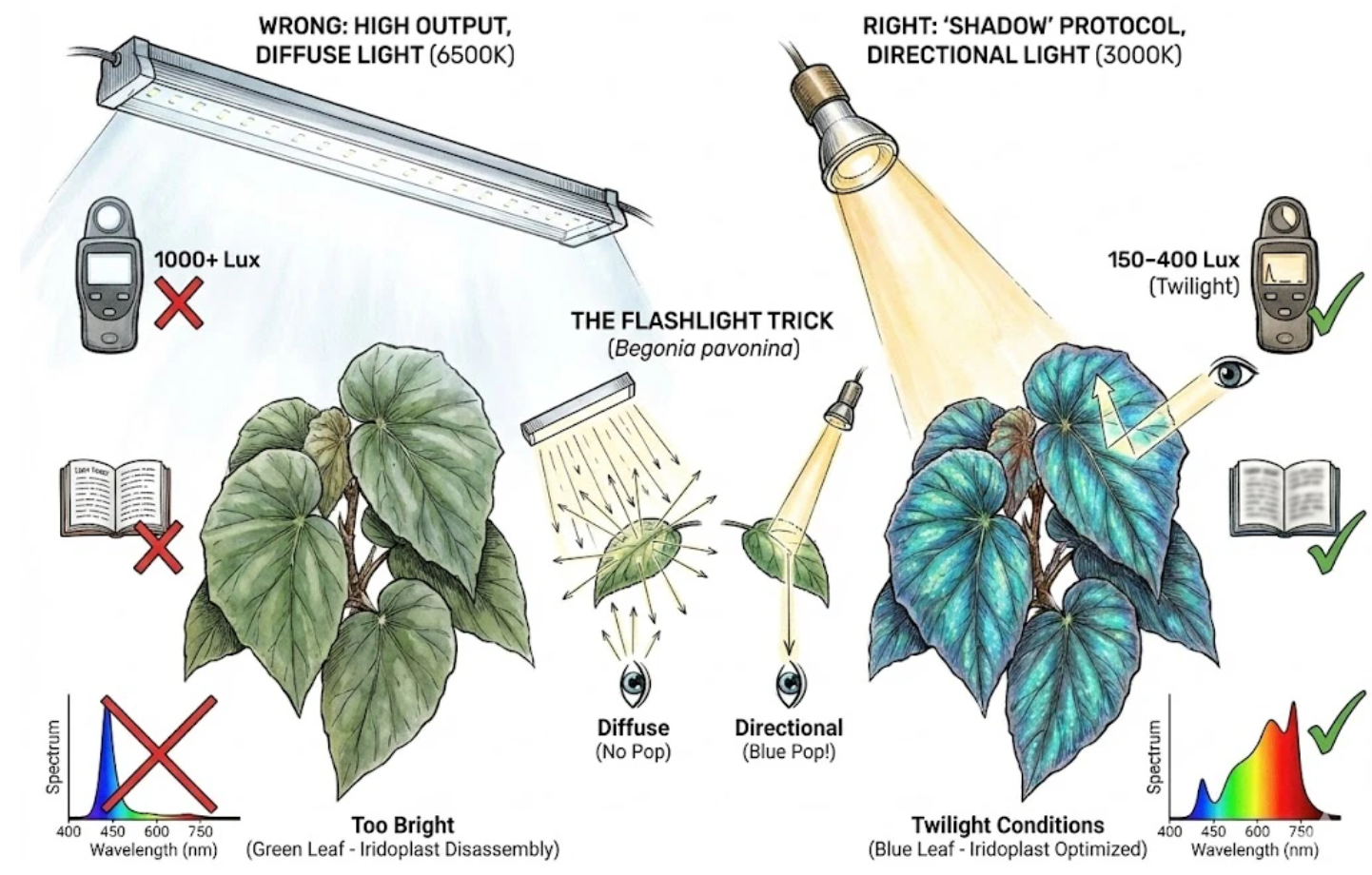

Optimal Light Conditions

Shade Mimicry: To mimic the understory environment where iridoplasts confer an advantage, begonias should be kept in moderately low light conditions - bright, indirect light but without full direct sun, especially midday.

Avoid Excessive Intensity: Too much direct sun can degrade the ordered thylakoid layering that produces structural colour and can suppress iridoplast expression.

Consistent Spectral Quality: A predominance of green over blue wavelengths - as occurs under canopy shade - appears most conducive to structural regularity in iridoplasts. Grow lights with broad spectrum outputs can support healthy growth while preserving these conditions.

Light Environment Comparison (For Growers)

Understanding light quality matters:

Begonia iridoplast development is tuned to shade-dominant environments.

These diagrams show how spectral quality and intensity differ between shade and full sun.

Grow lights with broad but moderate spectrum can mimic ideal conditions.

Temperature and Humidity

Although iridoplasts themselves are light-driven adaptations, general plant health is critical:

Maintain tropical to subtropical temperature regimes (18–26 °C).

Ensure high humidity approximating understory conditions - iridoplast-bearing species originate from equatorial forests.

Nutrition and Watering

Moderate fertilisation supports vigorous leaf development, which indirectly supports plastid development.

Avoid water stress, as drought can reduce leaf expansion and may disrupt plastid development.

Light Acclimation Practices

Some growers have reported stronger iridescence when begonias are acclimated to slightly lower average light over extended periods rather than abrupt changes. While peer-reviewed studies on cultivation specifics are limited, the plasticity observed in controlled experiments supports this strategy (3).

So, how to make the most of your blue Begonias? Keep the light levels lower to promote the stability of iridoplasts, support humidity levels to maintain turgidity, and remember that the iridescence is directional and seen under a single light source such as a torch or spotlight.

Iridoplasts represent a remarkable example of plant adaptation to photic environments. Far from an aesthetic novelty, these specialised chloroplasts embody structural photonics evolved to enhance photosynthetic performance under extreme shade. Research shows that in Begonia, iridoplasts are widespread but only visually obvious in a subset of taxa; their photonic architecture is both functional and plastic, responding to environmental light conditions.

For horticulturists, understanding the environmental cues shaping iridoplast development - especially light intensity and quality - can help cultivate begonias that express their iridescent potential. This intersection of evolutionary biology, plant physiology, and practical cultivation illustrates the depth of insight to be gained from integrating basic research into everyday gardening practice.

Want to increase your collection of Begonias showing off their iridoplasts? Here are some great options:

pavonina

metallicolor

kapuashuluensis

erythrofolia

sp. ‘Sarawak’ and lichenora

aketajawensis

burkillii

iridescens

U485

‘Robin’

daunhitam

sizemoreae

sp ‘Tuyen Quang’

Austrovietnamica

sp. ‘Sumatera’

Key References

Chaffey N. Iridoplasts, out of the shadows at last. Botany One. 2017.

How some plants adapt to shade. Nature 538, 431 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1038/538431a

Jacobs M, Lopez-Garcia M, Phrathep O-P, Lawson T, Oulton R & Whitney HM. Photonic multilayer structure of Begonia chloroplasts enhances photosynthetic efficiency. Nature Plants. 2016.

Lundquist CR, et al. Living jewels: iterative evolution of iridescent blue leaves from helicoidal cell walls. Annals of Botany 2024 Mar 29;134(1):131–150.

Pao SH et al. Lamelloplasts and minichloroplasts in Begoniaceae: iridescence and photosynthetic functioning. Journal of Plant Research. 2018.

Phrathep O. Biodiversity and physiology of Begonia iridoplasts. PhD thesis, University of Bristol. 2020.

Further Reading

Photonic multilayer structure of Begonia chloroplasts enhances photosynthetic efficiency

Lamelloplasts and minichloroplasts in Begoniaceae: iridescence and photosynthetic functioning

Begonia hahiepiana, a New Species of Begonia Section Sphenanthera (Begoniaceae) from Vietnam

Metallic Blue Leaves Of Begonia Pavonina Help Tropical Plant Survive In Dark Rainforests

Insights into the Evolution of the Chloroplast Genome and the Phylogeny of Begonia

Blue Foliage Plants: The Photonic Engineering of Iridescent Leaves